By Bill Scott, President, StoreReport

Convenience store operators tend to live in the present—How much will I sell today, this week, this month, this year—and put little or no effort in forecasting. Forecasting is easy, IF you have the tools to do it.

Forecasting may consists of multiple systems addressing multiple objectives. For example, merchandise planning, labor management, planograms, replenishment and allocation – each deserve a slightly different approach.

In short, forecasting should be a single objective driving multiple actions

Grocery stores, having huge categories, may use forecasting to forecast the performance of categories in a non-product specific environment. Small retailers, like convenience stores, may have categories subdivided into types such as general merchandise and household items, and items like chips, cookies, candy, etc., and are more suited to forecast by specific items.

Although Category Management (CM), with regards to smaller retailers, may be important in determining and maintaining product mix, once the proper mix has been established, CM provides no help whatsoever in forecasting. ‘Demand forecasting’ is a far better method that forecasting at the category level.

Demand Forecasting uses three major sources of history. The first consisting of orders generated for the stores and/or inventory receipts. The second is the scanned data from the Point-Of-Sale (POS, or cash register). The third source is frequent and timely audits.

In order to be accurate, these functions must occur in real time, else the disposition of the inventory will always be in question, and that contributes to over-stock and out-of-stock situations.

Suppliers have a bad habit of replicating the last order with no regards to the actual stock on hand in the store, oftentimes selling the store inventory it does not need. Don’t blame your suppliers. You taught them that’s what you want. The problem is that your suppliers may have to supply thousands of stores just like yours that are as different as night and day. Similar, but different. Every store has its own unique footprint, but all your suppliers sees is another retail store that needs to be filled.

Not being able to forecast future requirements, put you and your supplier at risk. Here are just a few examples.

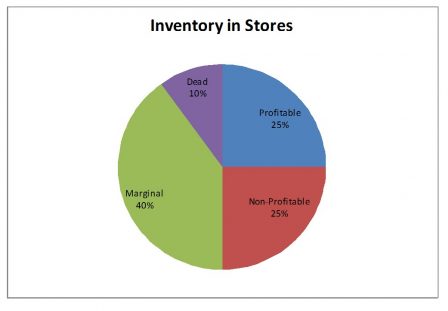

It’s estimated that the average convenience store has 100% more inventory than needed to meet customer demand. Given a limited amount of space, this means the average store should be able to operate in 50% less space, or it could double its product lines, which might suggests a re-engineering of the stores’ shelves.

Too much inventory is occupying too much space in a too small store, and your customers are being punished for it. They are punished by how much they pay for your goods, and how much trouble it takes them to find what they want. ‘Convenience’ has become ‘inconvenience’. But you are also punishing yourself.